Rural credit is the primary climate finance instrument for land use in Brazil, amounting to an average of US$ 3.2 billion/year between 2015 and 2020. This value, however, represents only 8% of all rural credit operations for the purposes of finance, investment, and industrialization in the country during this period, which averaged US$ 42.2 billion/year.[1]

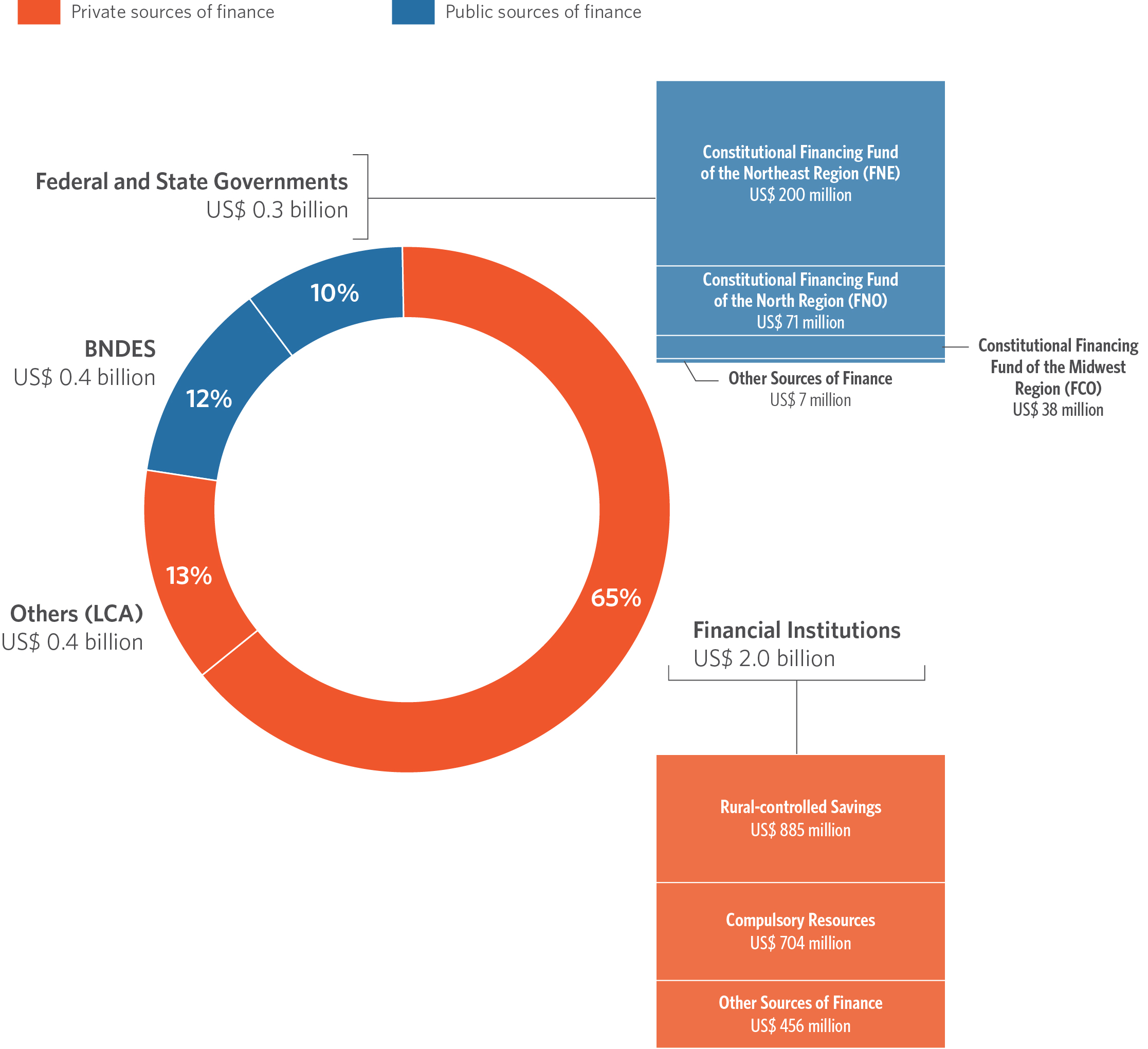

Private finance from financial institutions that operate rural credit – which include public and private banks and credit cooperatives – amounted to US$ 2.0 billion/year (65%) of climate- aligned rural credit, as shown in Figure 4. When operating rural credit, financial institutions need to follow a set of rules established by the country’s main agricultural policy, the Brazilian Agricultural Plan (Plano Safra).[2] One such rule mandates financial institutions to allocate part of the deposits in their checking and savings accounts to rural credit.[3] This mandate applies to public and private sources, which explains the relatively high share of climate-aligned rural credit originating from the private sector.

Figure 4. Climate Finance of Rural Credit in Brazil by Source of Finance, 2015-2020

Note: The values refer to the average amount in Brazilian Real (R$) during the analyzed period, deflated by the IPCA using December 2020 as reference. The values were converted into United States Dollar (US$), according to the average exchange rate for the corresponding year, as provided by the Central Bank of Brazil (Banco Central do Brasil – BCB).

Source: CPI/PUC-Rio with data from SICOR/BCB, 2023

Public finance accounted for US$ 700 million/year (22%) of climate flows in rural credit. BNDES was the main source of public finance at US$ 386 million/year (12%). Constitutional Finance Funds (Fundos Constitucionais de Financiamento – FCFs) also played a prominent role, having directed, jointly, US$ 314 million/year (10%) of the finance tracked in the period through rural credit, broken down as follows: US$ 199 million/year from the Constitutional Financing Fund of the Northeast Region (Fundo Constitucional de Financiamento do Nordeste – FNE), US$ 71 million/year from the Constitutional Financing Fund of the North Region (Fundo Constitucional de Financiamento do Norte – FNO) and US$ 37 million/year from the Constitutional Financing Fund of the Midwest Region (Fundo Constitucional de Financiamento do Centro Oeste – FCO).

The Brazilian Agricultural Plan regulates the sources of finance, the amounts allocated to each credit line, and the main conditions to finance crop and cattle activities for the purposes of funding, investment, trade, and industrialization. In fact, there is a wide range of finance sources and programs for rural producers under different finance conditions. The complexity of the rules leads to artificial variations in finance available for credit, giving rise to distortions and inefficiency (Souza, Herschmann and Assunção 2020).[4]

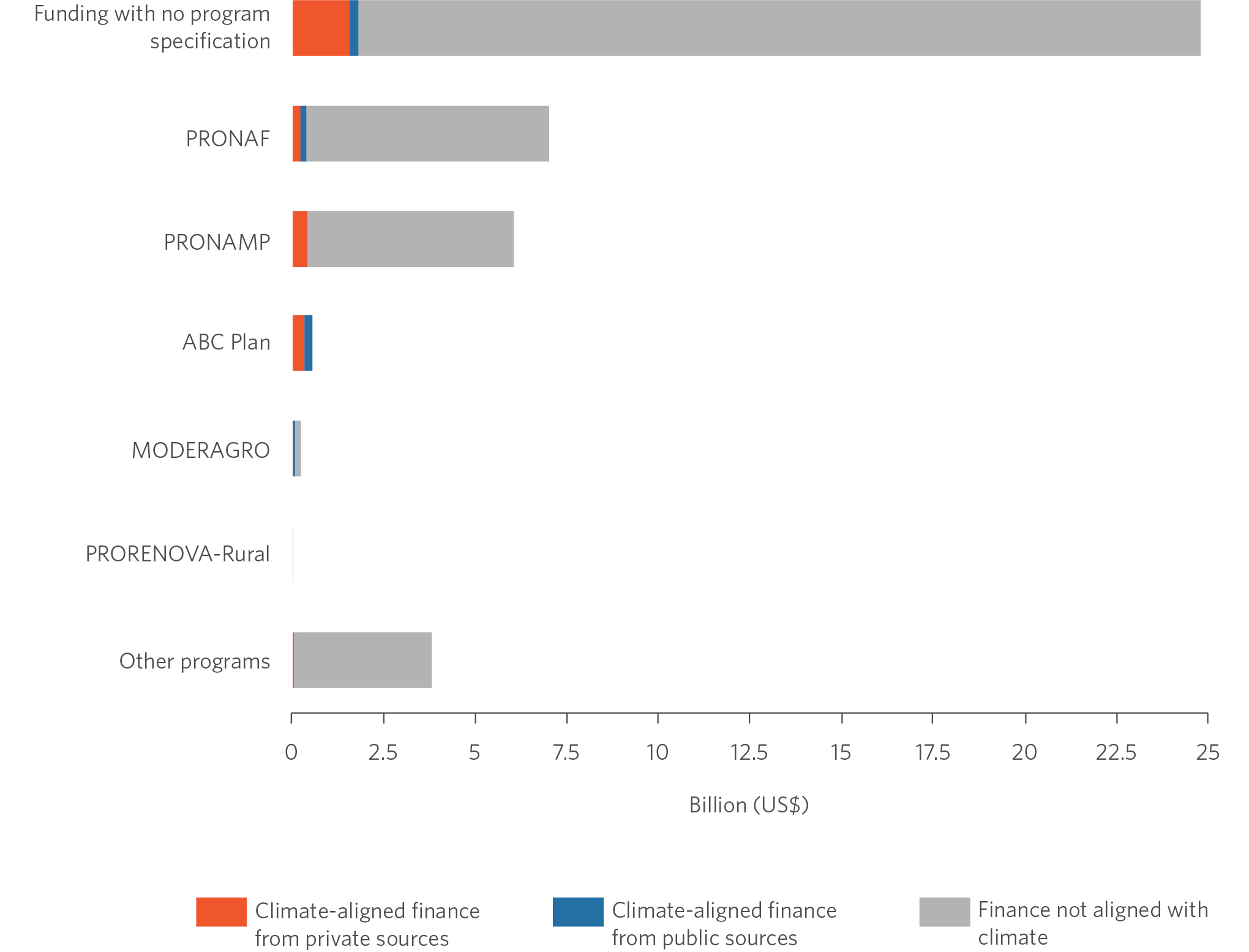

Figure 5 shows climate finance for land use in Brazil by rural credit line. The National Program for Low-Carbon Emissions in Agriculture – ABC Program (Programa para Redução da Emissão de Gases de Efeito Estufa na Agricultura – Programa ABC) was the main rural credit line contributing to climate finance in that period. This line was created to achieve the objectives of the ABC Plan, the main government initiative to reduce emissions and promote the adaptation of the agricultural sector to climate change, prepared for the decade from 2011 to 2020. The plan is currently in a new phase, called ABC+ Plan, to be implemented between 2021 and 2030. In the Brazilian Agricultural Plan for 2023/2024, the investment lines for the ABC Program have been renamed and are now part of the newly created Program for Finance Sustainable Agricultural Production Systems (Programa para Financiamento a Sistemas de Produção Agropecuária Sustentáveis – RENOVAGRO) (MAPA 2023).

Figure 5. Climate Finance for Land Use in Brazil by Rural Credit Line and Source of Finance, 2015-2020

Note: The values refer to the average amount in Brazilian Real (R$) during the analyzed period, deflated by the IPCA using December 2020 as reference. The values were converted into United States Dollar (US$), according to the average exchange rate for the corresponding year, as provided by the Central Bank of Brazil (Banco Central do Brasil – BCB).

Source: CPI/PUC-Rio with data from SICOR/BCB, 2023.

Between 2015 and 2020, an average of US$ 539 million/year was channeled via the ABC Program, which represents 17% of tracked climate finance flows via rural credit. This credit line corresponded to only 1% of the total annual amount for rural credit operations.[5]

Nevertheless, most of the climate finance via rural credit was not linked to a specific program, corresponding to US$ 1.8 billion/year (56%). Furthermore, US$ 396 million/year (13%) were channeled by the National Program to Support Medium-Sized Rural Producers (Programa Nacional de Apoio ao Médio Produtor Rural – PRONAMP)[6], credit line that serves medium-scale rural producers, while US$ 333 million/year (11%) were channeled by the National Program for Family Farming (Programa Nacional de Fortalecimento da Agricultura Familiar – PRONAF)[7], a credit line geared towards family farmers.

One challenge involves identifying the final beneficiaries of climate finance channeled via rural credit. The data do not allow for quantifying the flows destined to indigenous peoples, quilombolas, and traditional communities.[8]

[1] Rural credit for trade purposes was not considered, as previously explained.

[2] The Brazilian Agricultural Plan is announced annually by the federal government. Specific conditions for the credit lines are subject to approval by the National Monetary Council (Conselho Monetário Nacional – CMN) and are recorded annually in the Rural Credit Manual (Manual de Crédito Rural – MCR) by the BCB (BCB 2023; Souza, Herschmann and Assunção 2020).

[3] The two main sources of finance for rural credit are mandatory resources – corresponding to 30% of current account deposits – and rural savings – where 65% of savings deposits in certain public banks and cooperatives are allocated to finance the rural sector. Financial institutions are also obliged to comply with sub-requirements and allocate a fraction of their funds to credit programs such as Pronaf (for family farming) and Pronamp (for medium rural producers) (Souza, Herschmann and Assunção 2020).

[4] In the 2020/21 crop year, the Brazilian Agricultural Plan set interest rates between 2.75% and 7.5% for credit controlled by the government, depending on the credit line, producer size and loan purpose (finance, investment, trade or industrialization). Government subsidies lead to lower interest rates than in the private market, which helps boost the use of credit.

[5] Rural credit for trade purposes was not considered, as explained above. The ABC Program has an investment purpose.

[6] PRONAMP beneficiaries are rural producers with at least 80% of their annual gross income derived from agriculture/vegetable extractive activities and whose annual gross income is up to US$ 596.

[7] In August 2023, according to the Rural Credit Manual (MCR 1-2-5E), small-scale rural producers and beneficiaries of PRONAF are considered to be those who earn up to US$ 99 thousand (according to average exchange in july of 2023) in Gross Annual Agricultural Revenue (Receita Bruta Agropecuária Anual – RBA) or who hold a Declaration of Aptitude for PRONAF (Declaração de Aptidão ao Pronaf – DAP) or a document from the – National Registry of Family Farming – National Program for Family Farming (Cadastro Nacional da Agricultura Familiar – Programa Nacional de Fortalecimento da Agricultura Familiar – CAF-PRONAF). These conditions are valid so long as the producer owns up to four fiscal modules of land (contiguous or otherwise) and that 50% of the household’s gross income come from agricultural activities. A fiscal module is a unit of measurement, expressed in hectares, whose value is set by the National Institute for Colonization and Agrarian Reform (Instituto Nacional de Colonização e Reforma Agrária – INCRA) for each municipality and corresponds to the minimum area needed for a rural property to be economically viable. The size of a fiscal module can vary significantly from one municipality to another (Souza, Oliveira and Stussi 2022).

[8] These types of beneficiaries are currently included under PRONAF’s definition of family farmers.

Here you can access the original blog post, the full report and an interactive Sankey on CPIs website.