Raising taxes during an economic downturn might seem counterintuitive but it could be the key to Covid-19 recovery. The secret lies in which taxes to raise: when it comes to impacts on the economy, jobs, and the environment, not all taxes are created equal.

The power of green tax reform is well understood in Europe. Part of the European Union’s “Fit for 55” package, a plan released last month to reduce the bloc’s carbon emissions by 55% by 2030, will increase minimum tax rates on the most polluting fuels and phase out exemptions on fossil fuels. The aim is to raise revenues by broadening the tax base while encouraging a move to clean energy.

For three decades, the Nordics (Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden) have already been using a “green tax shift” in response to economic crises. Taxes on pollution and polluting sectors generated revenues that allowed governments to reduce taxes that are a drag on productivity, like on labour and capital. This drove down pollution, while investment in clean energy boomed.

Finding policy solutions that address the twin challenges of economic growth and climate change is critical for a fossil-free recovery. Raising certain taxes is part of the solution, not the problem.

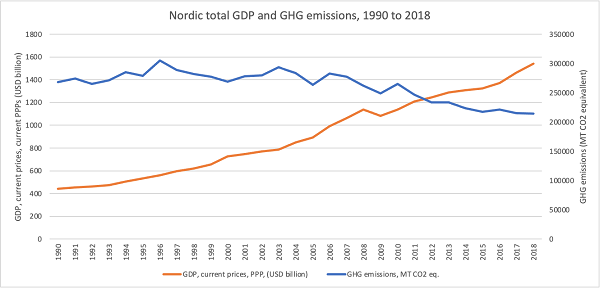

Denmark, Finland, Sweden and Norway introduced carbon taxes in the early 1990s in response to a regional economic crisis. Iceland followed suit in 2010 in response to the 2008 global financial crisis. While it’s hard to attribute economy-wide outcomes to a single policy, the Nordics saw their economies grow while their greenhouse gas emissions fell.

Current GDP and greenhouse gas emissions for Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Sweden and Norway

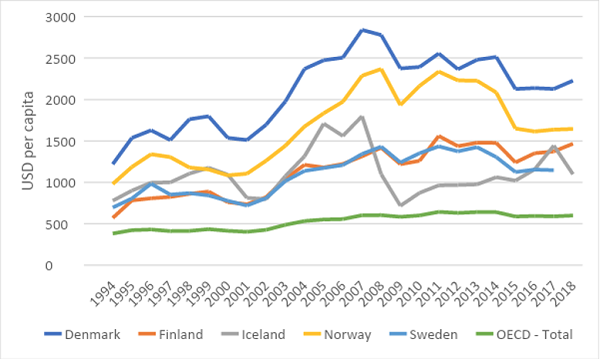

Energy, transport, and pollution taxes boosted budgets significantly. Most Nordics collected between $ 7 billion and $13 billion from environmental taxes in 2018. All Nordics have at least double the environmental tax per capita as the OECD average, with Denmark’s being over four times higher.

Current Revenue per capita from environmental taxes in Nordic countries compared with OECD average

These revenues resulted in a shift in the tax burden from workers and businesses to polluting activities. For example, Sweden’s carbon tax was accompanied by cuts to personal income, property, and wealth taxes, as well as businesses’ social security contributions. Sweden’s overall tax level fell from over 50% of GDP in 1990 to 44% in 2018. So while citizens pay more for some carbon-intensive products like fuel, they pay less in other taxes, meaning family budgets do not suffer.

While evidence shows that a green tax shift could be the most sustainable and strategic way to recover from the pandemic, raising pollution taxes has been the exception, not the rule. Only Costa Rica, India and the Philippines raised fuel taxes to fund the pandemic response. So why aren’t more countries following the Nordic example? There is a misconception that higher taxes will take money from people’s pockets and cut jobs. But the opposite is true: done right, increasing environmental taxes can create opportunities in economies of all sizes

In 31 European countries participating in the EU emissions trading system, research found no evidence of adverse effects on GDP growth from environmental taxes. Following Sweden’s green tax shift, average disposable income grew four times faster in 1995 than during the previous twenty years. In Iceland, GDP per capita rebounded with a staggering 77% growth from 2009 to 2018.

Green taxes, if accompanied by job creation programs and tax cuts on labour, can actually result in net job creation, including sustainable jobs in clean energy. Denmark’s world-class wind industry was supported by fiscal reforms and now employs more than 33,000 people.

Due to three decades of price signals that promote low pollution and low carbon, Nordic countries have already completed energy and economic transitions that other countries are struggling to start. For Sweden, one unit of GDP emits just 32% of the OECD average. Meanwhile, Norway reduced GHG emissions per dollar GDP despite being home to a significant oil and gas industry.

Lessons can be drawn from the Nordic experience that are relevant to all countries seeking to boost government budgets while addressing pollution. Green tax reform can be adapted to suit local tax infrastructure, pollution priorities, and desired outcomes. The key principles are “the polluter pays” and that tax revenue must be spent productively. Green taxation policies, especially during an economic crisis, must be built in a way that improves quality of life for all. Clearly communicating the benefits can raise the political support needed for reform.

Governments can’t afford to miss this opportunity to transition their economies. Countries that align their recovery plans with green taxation today will be ahead of the curve tomorrow. The evidence shows that raising revenue from energy taxes, and spending it wisely, would fast-track climate compatible development while creating economic opportunities.

Tara Laan is a senior associate with the International Institute for Sustainable Development’s energy program and leads their energy taxation work.

This article was originally published by Climate Home News.