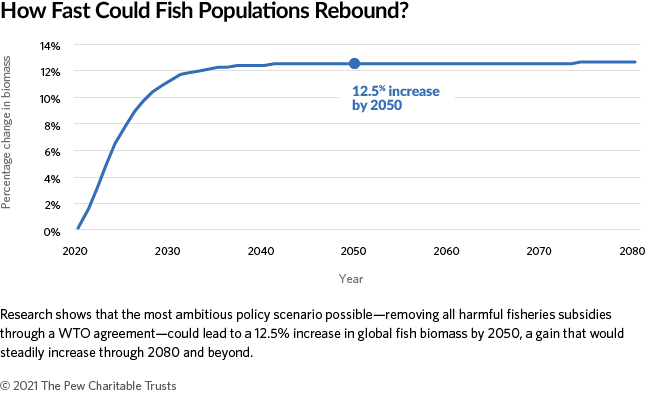

A World Trade Organization deal to cease destructive payments would yield 12.5% rise by 2050

Overfishing presents one of the greatest threats to the health of the global ocean. Estimates from the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) suggest that 34% of fish populations worldwide are exploited beyond biologically sustainable levels.

Some fisheries subsidies—payments that governments make to the fishing industry—are a key driver of this overfishing, and new research has found that eliminating all of these harmful subsidies could help fish populations recover. Specifically, ending all destructive subsidies would result in an increase of 12.5% in global fish biomass by 2050, which translates into nearly 35 million metric tons of fish—almost three times the entire continent of Africa’s fish consumption in a single year.

These figures are derived from a bioeconomic model—funded by The Pew Charitable Trusts—that scientists at the University of California, Santa Barbara, created using publicly accessible data from 2018, the most recent year for which complete data was available. The model was peer-reviewed by independent economists, and later shared with World Trade Organization (WTO) members who are currently negotiating a global agreement that could end all damaging subsidies and help fish populations achieve the significant rebound forecast by the tool.

Right now, governments around the world spend $22 billion each year in harmful payments to their fishing sectors. This money allows fleets to continue fishing even when market and operating conditions, such as dwindling catch, indicate they shouldn’t.

The WTO began negotiating fisheries subsidies reform two decades ago, and last year members were poised to strike a deal to eliminate these payments—and meet the deadline they committed to under the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal 14, Target 6. Unfortunately, WTO members missed their 2020 deadline primarily due to pandemic-related delays in the negotiations process. With no agreement in place, fish stocks continue to be overfished, underscoring the urgency with which the WTO must now act.

As talks continue, WTO members are using this model to compare the different policies that are under negotiation to explore how global and regional fisheries would respond to reform—for instance, by rebounding or being further depleted. Members are also using the tool to access a repository of fishery information.

The model takes vessel, fishery, and subsidy data from around the world and simplifies it to represent one global fishery and three regional fisheries: one each in the Atlantic, Indian, and Pacific oceans. A user can then select one of the proposed reforms the WTO is considering and see that policy’s potential impact on the amount of fish in the water (biomass), revenue from fishing, and global or regional catch levels, which can differ from one another. For example, if WTO members eliminate all harmful subsidies, the model shows that fish biomass in the Pacific could rise by 19.3% by 2050—an even greater jump than the global increase.

Scientists built the tool using data from sources such as the FAO global catch database, historical fish catch prices, the Global Fishing Watch database, and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s fisheries support estimate database. Although the model accounts for a wide range of factors, the results of subsidies policy reform will likely vary from region to region because of variances in how nations run their subsidy programs, the condition of individual fish stocks, the complexity of fisheries management systems, and how fisheries respond to reform.

But one thing is clear: This model shows that ending harmful subsidies can help reduce overfishing and at least begin to reverse some of the damage it has done to our ocean. And that should persuade WTO members to swiftly reach an agreement on this vital issue and deliver good news to the billions of people worldwide who depend on healthy fisheries and a fully functioning marine ecosystem.

Ernesto Fernandez Monge is an officer and Reyna Gilbert is a senior associate with The Pew Charitable Trusts’ reducing harmful fisheries subsidies project.

This article was originally shared by Pew Charitable Trusts.