About the Author:

Murray Petrie has wide experience as a public official, international civil servant, consultant, civil society activist, and academic researcher in public financial management and governance. He has published widely in these areas and is a member of the IMF’s Panel of Fiscal Experts, the OECD Expert Group on Green Budgeting, and is Special Advisor to the Global Initiative for Fiscal Transparency. He has an M.A. (Hons.) in Economics, a Master of Public Administration from Harvard, and a Ph.D. in Public Policy from Victoria University of Wellington, where he is a Senior Research Associate at the Institute of Governance and Policy Studies. In a new book Murray Petrie puts forward a comprehensive framework in answer to the increasingly urgent question: how can governments be made more accountable for their environmental stewardship? This blog draws from the book.

Current approaches to environmental stewardship are demonstrably failing given the existential threats of climate change and biodiversity loss. Many factors contribute to global environmental degradation, but one that has received relatively little attention is the lack of government transparency and accountability for environmental stewardship compared to other policy domains, and the systematically weak integration of environmental stewardship into overall government strategy and target setting.

In 1987 the Brundtland Commission called for the major central economic agencies of governments to be made directly responsible for ensuring that their policies and budgets support ecologically sustainable development. There has, however, been precious little progress in that direction since.

The weak governance of environmental stewardship stands in stark contrast to the governance of fiscal and monetary policy. For instance, over the last thirty years governments have increasingly managed the public finances based on commitments in domestic law to publish goals, targets, and milestones and to report regularly on progress.

There are three inter-related areas where action to promote environmental sustainability is urgently

required:

- National ‘State of the Environment’ reporting to regularly measure the state of the environment and highlight the most important risks to sustainability.

- Environmental target setting and regular progress reporting, and the integration of these in government strategic planning and in a dashboard of core national indicators of social, environmental, and economic progress.

- Using a government’s most important policy statement and its most powerful strategy and policy integration instrument – fiscal policy and the annual budget cycle – to mainstream environmental goals, to progressively eliminate environmentally harmful tax and expenditure policies, and to promote environmentally sustainable development.

Why are these three actions crucial to environmental sustainability?

- In the current system of sovereign nation states it is only national governments (and the subnational jurisdictions within them) that can make and enforce the decisions required for environmental stewardship (with the partial exception of the EU). Planetary or regional boundaries can in the main only be managed at the national level.

- While many corporates are adopting strategies to cut emissions and to invest in nature only governments have the tools to change behaviour throughout an economy to bring about the transformational changes needed at the required scale and speed.

- Publication of regular independent national State of the Environment Reports is required to provide the physical outcomes data needed for environmental stewardship. Yet there are serious weaknesses in national environmental reporting, where it exists: it is the poor cousin of economic statistics and the reports have limited visibility or impact on decisions. The leading framework of national State of the Environment Reporting (DPSIR) is predominantly backward looking, resulting in inadequate attention to environmental risks.

- There is an urgent need to apply to national environmental stewardship a broadly comparable underlying framework of outcomes measurement and reporting, transparency of time-bound targets, and ex-post accountability. Prompted by international climate change treaties, this approach is increasingly being applied by governments to greenhouse gas emissions. This general approach is required across all key environmental domains – like the approach in Sweden to setting environmental quality objectives (and the approach embodied in the current UK Environment Bill) – drawing on baseline data in national State of the Environment Reports to set targets for the most critical environmental indicators.

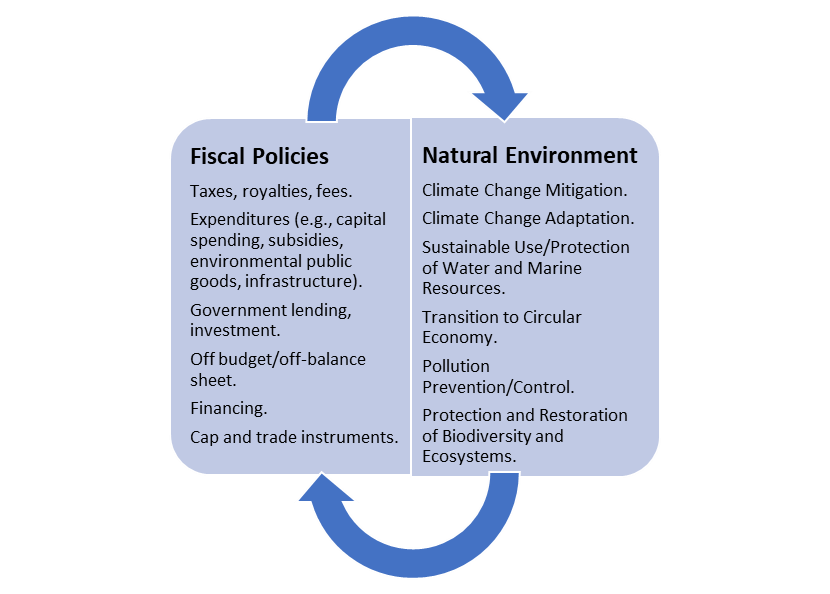

- There are increasingly important actual and potential impacts of fiscal policies on the environment, both environmentally harmful and beneficial, and environmental degradation has growing fiscal impacts and poses escalating fiscal risks – see Figure 1 (the environmental outcomes are based on the EU taxonomy of sustainable environmental outcomes). Yet fiscal strategy setting around the world remains dominated by assessment of macroeconomic and fiscal statistics and associated risks. Environmental considerations need to be fully and transparently incorporated in government strategy, and in the criteria used in making decisions on fiscal policy and budget allocations.

- While regulation is critically important for environmental stewardship there is no annual regulatory policy cycle or process that could integrate and mainstream environmental goals in government strategy and cross-sector prioritization. And in countries with multi-year national planning frameworks these must be implemented largely through annual budget allocations for public investment projects. In addition, there are important environmental policy tools that are hybrids of fiscal and regulatory interventions e.g., emissions trading schemes; and government policy increasingly needs to consider complex smart packages of

regulatory and fiscal interventions.

The greening of fiscal policy is therefore the key tool to mainstream environmental objectives, targets, and instruments in government strategy and policy and to make governments more accountable for environmental stewardship.

This will require the progressive incorporation of environmental objectives, targets, analysis, and filters across the budget cycle, in tax policy, and in the public investment management cycle. Key entry points for the greening of fiscal policy include:

- The new policies in the annual budget (and COVID recovery packages) and assessing their consistency with national and international environmental commitments and targets e.g., Nationally Determined Contributions.

- The on-going tax and expenditure policies that are known to be the most environmentally damaging, such as subsidies for fossil fuels.

- Taxing environmental externalities and earmarking the proceeds (including from cap-and- trade schemes) to public expenditure programs e.g., to fund mitigation, adaptation, transitional assistance to those most adversely affected by green taxes.

- Integrating climate and the environment across the public investment management cycle to prevent locking-in high emissions and environmental damage and to avoid wasting scare resources in the form of stranded assets.

- Introducing climate (green) budget tagging for countries seeking to attract international climate (green) finance.

- Conducting periodic Green Spending Reviews and Green Tax Reviews.

- Cross-national benchmark indicators.

- Identifying, analysing, mitigating, and disclosing fiscal risks from the environment.

- The performance (outputs and results) of environmentally relevant expenditure programs e.g., conservation programs, biodiversity preservation, waste management, invasive species control.

- The accountability framework for public corporations, and the oversight framework for sub-national governments.

It will also be important to:

- Ensure a high degree of transparency and accountability by progressively presenting a range of supplementary green budget documents and periodic green fiscal reports to the legislature and the public, including at the time of presentation of the annual budget proposal.

- Directly engage the public, including traditionally excluded or marginalised voices, in debate and deliberation on the design and implementation of fiscal policies and frame policy issues and public debate in ways that promote environmental sustainability.

- Enable civil society including the media to actively monitor governments’ environmental stewardship, call out ‘green washing’, and promote the public interest over the interests of elites, including through new civil society-initiated tools such as a Green Guide to the Budget and a new Index of Environmental Governance.

- Invest in capacity development in the executive (especially in ministries of finance and environment ministries), the legislature, the Supreme Audit Institution, and civil society, in national State of the Environment monitoring and reporting, environmental tax and expenditure analysis, and in green disclosure and public engagement.

References:

Murray Petrie, 2021. Environmental Governance and Greening Fiscal Policy: Government

Accountability for Environmental Stewardship: https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-030-

83796-9#tocpecial.