About the Authors

Erin Campbell

Originally from Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, Erin graduated from the University of Rochester in May 2021 with a B.S. in Environmental Health, B.A. in Economics, and a minor in statistics. Her primary research interests are environmental justice related, but she has a knack for finding just about anything fascinating if she reads enough about it. Throughout her time in Rochester, Erin was involved in both independent and mentored research in the department of economics where she discovered her passion for applying the tools of econometrics to today's most pressing issues. Erin is a proud AmeriCorps alum, and prior to RFF she experienced many avenues of research at the USDA, Bipartisan Policy Center, and the Health and Environmental Economics Lab at the University of Rochester.

William Pizer

Billy Pizer is Vice President for Research and Policy Engagement at RFF. Previously, he was the Susan B. King Professor at the Sanford School of Public Policy, Duke University. He is also a Research Associate at the National Bureau of Economic Research. His past and current research examines how we value the future benefits of climate change mitigation, how environmental regulation and climate policy can affect production costs and competitiveness, and how the design of market-based environmental policies can address the needs of different stakeholders. He has recently begun work examining the potential role of solar radiation management (injection of aerosols in the stratosphere) in climate change policy, in addition to mitigation and adaptation. He is currently a member of the NASEM Committee on Accelerating Decarbonization in the United States.

Border carbon adjustments (BCAs) attempt to impose additional costs on imported, carbon-intensive products. The goal of such policies is to both reduce global greenhouse gas emissions and avoid unfair trade advantages when one country pursues more ambitious climate change mitigation policies than its trading partners. Without BCAs, incentives exist for businesses to shift production to less-regulated countries where it’s easier to pollute.

The basic idea of BCAs in the case of an emissions trading scheme (such as the European Union’s Emissions Trading System) or carbon tax is to ensure that foreign producers face the same incentives to reduce their emissions, and the same charges for emissions, as domestic producers. Overall, the design of a BCA is relatively straightforward: Absent a foreign carbon price, apply the full domestic price to emissions associated with imported goods. With a nonzero foreign price that’s lower than the domestic price, apply the difference.

Myriad design questions can be applied to BCAs; the incentives are inherently imperfect and involve trade-offs. For example, to create similar incentives for imports as for domestic products, policymakers would need to tie the BCA to the carbon content of the actual imported good, rather than the average carbon content within a foreign firm or industry. But such a policy would create strong incentives for countries and firms to export only their cleanest goods, without necessarily reducing the carbon content of all their goods. In addition, questions remain over whether BCAs comply with international trade rules. Finally, one would hope that BCAs create incentives for trade partners to enact stronger climate policies and avoid the BCA—but it is also possible that BCAs will sow distrust and discourage action.

But these questions become more complex in the case of a country like the United States, which employs a mix of climate policies but does not currently have a formal carbon price, or in a program such as the EU Emissions Trading System that gives significant free allocation (emissions allowances granted outside of a traditional auction) to energy-intensive, trade-exposed industries where allocation is progressive. This added complexity raises the question of how a BCA might work with a “partial-price” or “non-price” policy. These partial-price policies include an explicit carbon price that is paid on some (but not all) of a firm’s emissions due to free allocation or some other allowance. Likewise, non-price policies are those in which emissions are regulated through a non-tradable standard, and no market price is observed.

How could BCAs be implemented under these partial-price or non-price policies? We explore this question in more detail in a new working paper, and the basics are clear: First, think about the structure of costs and incentives under the suite of domestic policies, and then seek to recreate those costs and incentives under the BCA. It’s a relatively new consideration, and the working paper serves as a starting point for conversations about BCAs in situations where traditional price policies are absent or play a smaller role than other climate policies that aren’t based on pricing.

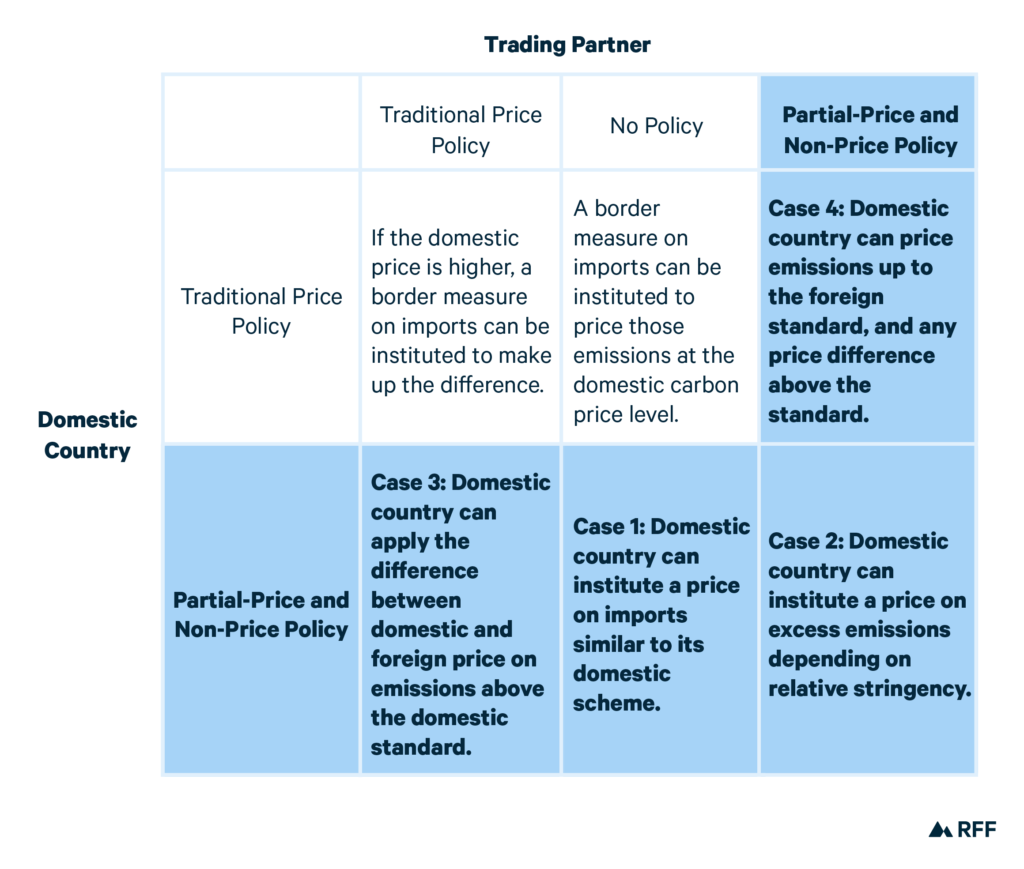

Different cases can arise between importers and their trading partners based on local policies (Table 1). A key piece to understanding the variety of cases is that, if BCAs are intended to apply the same incentives and costs to trading partners as the incentives and costs that arise for domestic producers, then the BCAs must avoid double counting any carbon emissions that are already priced or otherwise regulated in the other country. The cells highlighted in blue (Table 1) represent the novel contributions of our working paper toward avoiding this double counting.

Table 1. Designing a Border Carbon Adjustment around Local Carbon Pricing Policies

Although we suggest in the working paper alternate ways to estimate BCA parameters in these cases of potential double counting, we note that implementation in practice likely will be difficult. For non-price policies, the particularly tricky part is estimating a price when no prices are observed. For partial-price policies, the tricky part may be establishing a benchmark for exempting foreign emissions before charging the BCA price. For example, free allocations may explicitly or implicitly “a benchmark rate at which charges begin, accounting for carbon emissions from the full life cycle of a building or infrastructure. But what should policymakers do when carbon pricing is only one component of a larger suite of climate policies?

Ultimately, BCAs effectively are tied to the differences among trading partners in terms of their carbon-related fiscal policies—in essence, how much firms are paying on net to the government for their emissions. Therefore, calculations of BCAs become more complicated than has been previously noted, in cases when BCAs try to replicate the incentives and costs of a suite of domestic policies.

Read the full working paper on the Resources for the Future website: Border Carbon Adjustments without Full (or Any) Carbon Pricing